Enjoy.

"In 35 years of medical research, conducted at the nonprofit Preventive Medicine Research Institute, which I founded, we have seen that patients who ate mostly plant-based meals, with dishes like black bean vegetarian chili and whole wheat penne pasta with roasted vegetables, achieved reversal of even severe coronary artery disease."

This claim - which is ubiquitous in the medical literature - is based on one study on 35 people, deemed the "landmark heart disease-reversal trial" by US News and World Report. 20 of the 35 people were randomized to receive the intervention which included consuming a low-fat vegetarian diet for at least a year. The diet consisted of fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, and soybean products without caloric restriction. No animal products were allowed except egg whites and one cup per day of non-fat milk or yoghurt; 10% of calories as fat, 15-20% protein, and 70-75% carbs. Cholesterol intake was limited to 5 mg/day. Subjects were also asked to practice stress management techniques at least 1 hour per day, exercise for at least 3 hours per week, and quit smoking if they were smokers. They also attended group meetings two times per week. The control group was given no guidance besides to continue following their own physician's advice.

After one and five years, the experimental group had less cardiac events, and a decrease in the size of the plaques in their coronary arteries.

This is perhaps one the most referenced studies in support of the protective effects of a low-fat diet, cited over 930 times (previous publication cited over 1500) according to Google Scholar, which is unfortunate due to the tremendous amount of confounding interventions. Along with an extremely low fat diet, the experimental group ate more fruits and vegetables, lost 23.9 pounds (control lost no weight), performed relaxation techniques 1 hour each day, exercised at least 3 hours a week, and had group counseling. The control group had none of this. The experimental group contained only 20 subjects (all male), and the control group had 15 (12 men and 3 women).

The small sample size resulted in an uneven distribution of risk factors between groups. At baseline, the mean age of the control group participants was 4 years higher, mean total cholesterol 8% higher and mean LDL 10% higher than those in the experimental group. Mean BMI was three points higher in the experimental group.

---

Dr. Ornish goes on to say that "in a randomized controlled trial, patients on this lifestyle program lost an average of 24 pounds after one year and maintained a 12-pound weight loss after five years. The more closely the patients followed this program, the more improvement we measured in each category — at any age."

This is a true statement, and a misleading use of the exact same clinical trial cited above twice, to likely add credibility to the argument. While they are two separate links, the linked "reversal of even severe disease" from above and this controlled trial cite the identical article on 35 people: Here and Here.

"Calories do count — fat is much denser in calories, so when you eat less fat, you consume fewer calories, without consuming less food. Also, it’s easy to eat too many calories from sugar and other refined carbs because they are so low in fiber that you can consume large amounts without getting full."

This argument is made over and over, reducing the complexities of the hormonal control and appetite regulation of the human body to simple arithmetic. The satiating nature of eating high fat, high protein diets cannot be over stated, and will have a much greater effect on subsequent eating behaviors than consciously ignoring our most basic physiological drive to eat when we are hungry, simply because we have reached our daily limit of fat calories mandated by the Ornish diet.

The satisfying, filling nature which lay the foundations for a Paleo or Atkins diet has been shown in clinical trials, and supported by literally thousands of people who have registered on the Ancestral Weight Loss Registry, from over 35 countries around the world. Based on the first 1,100 people to register, 95% report rarely or never feeling hungry between meals and 88% reported feeling less hungry than on a low-calorie diet (if they had tried it in the past). If you do not believe these stats, then you can read the hundreds of stories from the people themselves:

"After a lifetime of being overweight... through childhood, the teen years, my twenties, thirties, and forties,... finally, at the age of 55, I experienced a "normal" appetite on a low carb diet. For all of those decades I "overate" because I was hungry...It certainly is NOT a problem of weak willpower."

"I was amazed how quickly my body adjusted to the new way of eating. In previous attempts to lose weight I had gone on low-fat, calorie-restricted diets that are based on 'mainstream' advice for weight loss. I would always be hungry and feel fatigued, and could never resist 'cheating' on my diets. On the low-carb diet, I rarely get hungry between meals and never feel fatigued. I weigh myself once a week. By the end of the first full month on the diet, I had lost twenty pounds."

"I ate an extremely low calorie diet for perhaps two years. I didn't follow any particular plan, I just avoided empty calories and counted calories carefully, limiting myself to about 1000 calories per day. I didn't eat an obsessively low-fat diet and I ate a lot of carbs I thought were healthy - rice, whole grain bread, potatoes. I was hungry all the time; I obsessed about food to the point that I planned every meal for several days in advance. I felt cold much of the time, especially at night. In addition, I fasted many weekends. Doing this, I was able to get down to a 34 inch waist."

"I've literally been on a diet all my life. Lost weight through calorie deprivation and also following the ill-advised low fat/high carb recommended by conventional wisdom and the U.S. government. I was always hungry with low energy. Eating that way was completely unsustainable for me."

"I was always hungry and thinking about food. Now on a low carb diet I eat without worrying about counting calories. It makes life easier."

Read literally hundreds more such quotes here, all of which are variations on a similar theme: Sudden lack of hunger on a diet high in meats, fats, and vegetables.

Dr. Ornish goes on to say:

"But never underestimate the power of telling people what they want to hear — like cheeseburgers and bacon are good for you. People are drawn to Atkins-type diets in part because, as the study showed, they produce a higher metabolic rate. But a low-carb diet increases metabolic rate because it’s stressful to your body. Just because something increases your metabolic rate doesn’t mean it’s good for you."

The cited study is the recent clinical trial done in a metabolic ward, in which the researchers explain: "Among overweight and obese young adults compared with pre-weight-loss energy expenditure, isocaloric feeding following 10% to 15% weight loss resulted in decreases in Resting Energy Expenditure (REE) and Total Energy Expenditure (TEE) that were greatest with the low-fat diet, intermediate with the low-glycemic index diet, and least with the very low-carbohydrate diet." In other words, the fewer carbohydrates in the diet, the higher the resting and overall expenditure, which was exciting news for the proponents of the Alternative hypothesis.

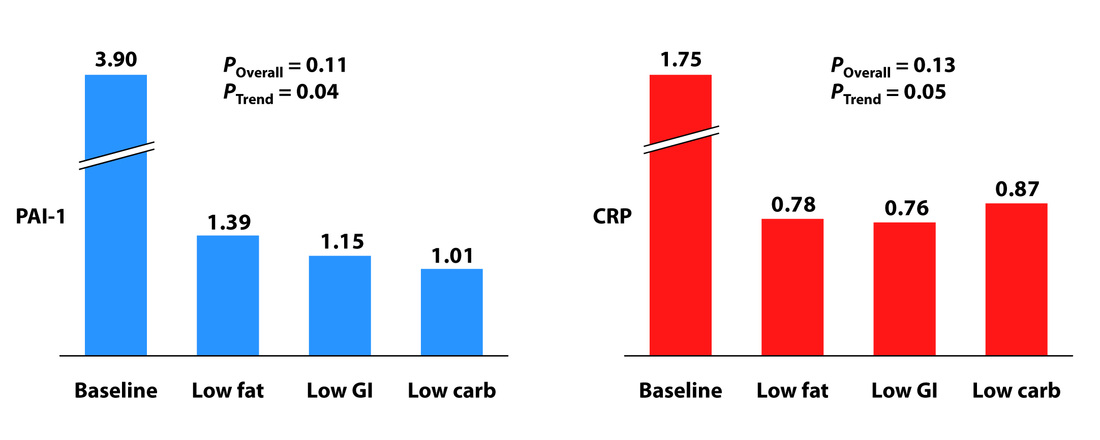

Dr. Ornish criticizes these results, explaining that "patients on an Atkins diet in this study showed more than double the level of CRP (C-reactive protein), which is a measure of chronic inflammation and also significantly higher levels of cortisol, a key stress hormone. Both of these increase the risk of heart disease and other chronic diseases."

As Dr. Peter Attia explains so eloquently on his blog, this is simply untrue. "Each group experienced a significant decline in both PAI-1 and CRP, and there was no significant difference between the groups for either marker. However, the trend was (barely) significant, favoring the low carbohydrate group for PAI-1 and favoring the low GI group for CRP. Sorry low fat, you didn't win either." As you can see in the graphs below, each group showed a reduction in CRP levels, just the Atkins group had a slightly smaller decrease than the other groups.

And what about these 14 clinical trials? How can the calorie unlimited, high fat diets keep producing more weight loss as compared to a low fat, calorie-restricted diet (at least in the short term), if they are characterized by high amounts of dietary fat, the vilified cause of obesity according to Dr. Ornish?

Even more striking is the fact that to our knowledge, a low-fat diet has NEVER in dietary clinical trial history produced more weight loss than a calorie unlimited, high fat diet. Many studies have shown no difference, but if it is true that a fat makes you fat, where are the clinical trials supporting this?

If you can find a randomized control trial in which a calorie restricted low fat diet produces more weight loss than a calorie unlimited high fat diet, please e-mail it to us and we will post it: [email protected].

Saturated Fat is Bad for you

Dr. Ornish says that "It’s not low carb or low fat," and then a few words later explains that an optimal diet is "low in fat (especially saturated fats and trans fats) as well as in red meat and processed foods."

While we can definitely agree that trans fats and highly processed foods should be limited, the saturated fat argument is an archaic one that is not supported in the literature and has become an academic argument perpetuated by selective citation of supportive trials and variations in inclusion criteria.

If we were to focus on the largest (i.e. > 100 subjects), randomized, most famous trials ever done lasting longer than 1 year, we are left with very few to assess that meet the following 2 criteria:

1) The only significant intervention involved a reduction in fat and saturated fat and an increase in polyunsaturated fats

2) They ask the question: does this diet reduce heart disease? (defined as heart attacks or death from heart disease)

Listed in reverse chronological order:

Women’s Health initiative (2006) – 48,835 women, 8 years, no significant difference between intervention and control.

Diet and Reinfarction trial (1989) – 2,033 men, 2 years, no significant difference between the groups given and not given fat and fiber advice. No significant differences in ischaemic heart disease between intervention and control (intervention was only advice in this trial)

Minnesota Coronary Survey* (1989) – 4,393 men and 4,664 women, double-blind, 4 years, no significant reduction in cardiovascular events or total deaths from the treatment diet

Finnish Mental Hospital (1972) – 12 years, physicians not blinded, significant decrease in coronary heart disease (CHD) death in men ( 5.7 deaths /1000 person-years vs 13 deaths /1000 person-years in the control. Non-significant decrease in CHD in women. (Not randomized, although included here because this is main experiment cited in support of diet-heart hypothesis)

Los Angeles Veteran’s Trial* (1969) – 846 subjects, up to 8 years, non significant difference in primary endpoints – sudden cardiac death or myocardial infarction. More non-cardiac deaths in experimental group, resulting in near identical rates of total mortality

Oslo Heart Study (1968) – 412 men, 5 year, slight decrease in CHD with intervention. Many dietary interventions accompanied the low saturated fat diet. When stratified by age, the results were significant only in subjects younger than 60.

* Double blind

A full list of all the trials done supporting and refuting the saturated fat-heart-disease relationship, and a more in depth description of each, can be found here.

Meta-analyses

If we instead focus on the recent meta-analyses of clinical trials testing this relationship, the majority have failed to elucidate a benefit associated with a low saturated fat diet:

- In 2010, Ramsden et al. published a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, including trials where polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) were increased in place of saturated fats (SFAs) and/or trans fatty acids (TFA), and non-fatal heart attacks, coronary heart disease related deaths, and/or total deaths were reported. In the nine studies included, there was a non-significant increased pooled risk of 13% for n-6 PUFA intake (RR=1.13, CI: 0.84, 1.53) and a decreased risk of 22% (RR=0.78, CI: 0.65, 0.93) for mixed n-3/n-6 PUFA diets. In other words, increasing polyunsaturated fats in the diet provides no benefit, and may be harmful according to this study.

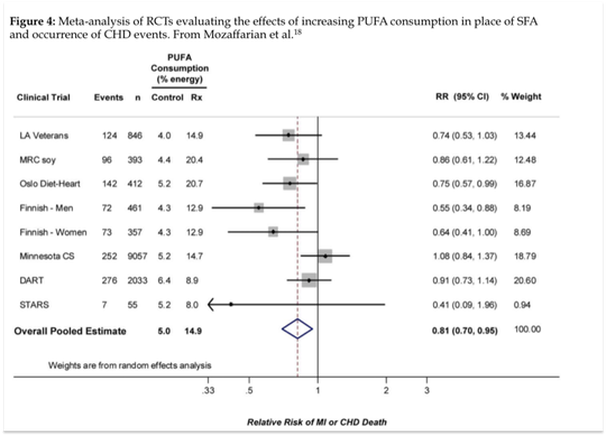

- Also in 2010, Mozaffarian et al published a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials investigating the effects of increasing PUFAs in place of other nutrients. Among the seven studies included, an overall pooled risk reduction of 19% (RR= 0.81, CI=0.83-0.97) was observed for each 5% of energy of increased PUFA in the diet.

- In 2009, Mente et al. published a systematic review of the randomized clinical trial (RCT) evidence that supports a causal link between various dietary factors and coronary heart disease. The pooled analysis from 43 RCTs showed that increased consumption of marine omega-3 fatty acids (RR=0.77; 95% CI: 0.62-0.91) and a Mediterranean diet pattern (RR=0.32, 95% CI: 0.15-0.48) were each associated with a significantly lower risk of CHD. Higher intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids or total fats were not significantly associated with CHD, and the link between saturated fats and CHD received a Bradford Hill score of only 2 (out of a maximum score of 4), signifying weak evidence of a causal relationship.

- Also in 2009, the Cochrane Collaboration, an international not-for-profit organization, published a meta-analysis of clinical trials that either reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease. Twenty-seven studies met the inclusion criteria, and no significant effect on total mortality (RR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.86-1.12) or cardiovascular mortality (RR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.77-1.07) was found between the intervention and control groups

The only study above showing a benefit to replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats was the Mozaffarian meta-analysis. The authors of the study claim to have only included randomized clinical trials in their meta-analysis. Surprisingly, the Finnish Mental Hospital Study was included twice – split into separate analytical pools of male and female subjects. It is unclear why this study was even included to begin with, since it was not randomized and contained a disproportionate number of control subjects who were taking cardio-toxic medications and consuming higher levels of trans fats than the experimental group.

Inclusion of male and female Finnish data separately further raises concern since it clearly exaggerates the apparent cardio-protective effect of PUFAs demonstrated in this meta-analysis. Excluding the Finnish data from their pooled analysis would diminish the observed results and elicit a null finding, since all other included studies apart from the Oslo heart study (RR=0.75, CI 0.57-0.99) were null:

In medical school we are taught how to take an HPI (History of present illness) whenever we see a new patient. The importance of this history is stressed in every class, because of how important the patient's story is, and how helpful it can be in coming up with the diagnosis.

Yet when it comes to figuring out why people are gaining weight, we don't listen. We are absolutely sure that the patient is at fault and we are correct: Just Eat less.

We don't listen to the fact that people are universally hungry on a calorie-restricted diet. Eat 500 less calories a day than you normally would, then run for an hour each day, then ignore your most basic physiological drive to eat when you get hungry. And repeat this for the rest of your life and our obesity problems will be solved.

What if instead there was a way of eating in which people ate when they were hungry, and stopped when they were satisfied. A way of eating which didn't force you to count calories. A way of eating that, based on our most rigourous scientific data available, produces the most weight loss, reduces triglycerides and increases HDL.

This way of eating exists, vilified by the medical community as "The Atkins diet", and relegated to a fringe movement and diet fad by the media as the "Caveman diet."

Yet when it comes down to which diet we should eat, the media, physicians and dietitians can make their case, but the final vote should be given to the patient. To the person actually eating the diet. If these patients from all over the world say they are no longer hungry, then maybe we should listen.

Tried a paleo or low carb diet? Join Today and contribute to a better understanding of this way of eating!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed