|

Related Science |

Saturated Fats and Heart Disease: Observational Studies

Some Points:

- The majority of prospective cohort studies found no correlation between saturated fat intake and heart disease

- Poor dietary assessment methods and large potential for bias create strong limitations to this data

- Focus should be placed on improving dietary patterns and not incriminating one specific nutrient

Summary:

Since the 1950s, saturated fat has been incriminated as the major dietary contributor to heart disease, attributed mainly to the fact that saturated fats have the ability to raise blood cholesterol. This temporary physiologic response to dietary fats led to the logical hypothesis that replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats, which lower blood cholesterol, may also lower coronary heart disease (CHD) rates, cardiovascular mortality, or both. This biological response to saturated fats has been the main reason diets high in meats carry such a stigma. The best way to determine if this hypothesis is true is through randomized, clinical trials. As discussed on our Saturated Fats & Heart disease – Clinical trials page, the evidence from the past 60 years has been inconclusive.

Yet conducting a large, long term trial is tremendously expensive and burdensome. For these reasons, prospective cohort studies offer an alternative design, although no causation can be determined. Subjects can be followed for a very long time and associations between their diets and disease can be illuminated. However, these observational studies (also known as prospective cohorts) have many short comings as well.

When researchers study the possible negative effects of saturated fats in prospective cohorts, they perform a baseline dietary intake measurement (usually a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), 24-hour recall, or 7 day food record), then follow subjects for up to ~25 years. The majority of them do not assess the diet anywhere in between. Just day one (or week one), and year 25.

In other words, What did you eat today, then in 25 years I will check to see if you died of heart disease. If you did, then I will correlate that with your diet the day I asked you what you ate.

Of course the likelihood that the baseline assessment is representative of their diet for the next 25 years is low. The best baseline assessments were 7-day food records, where subjects meticulously weigh and record everything they ate. These were rare.

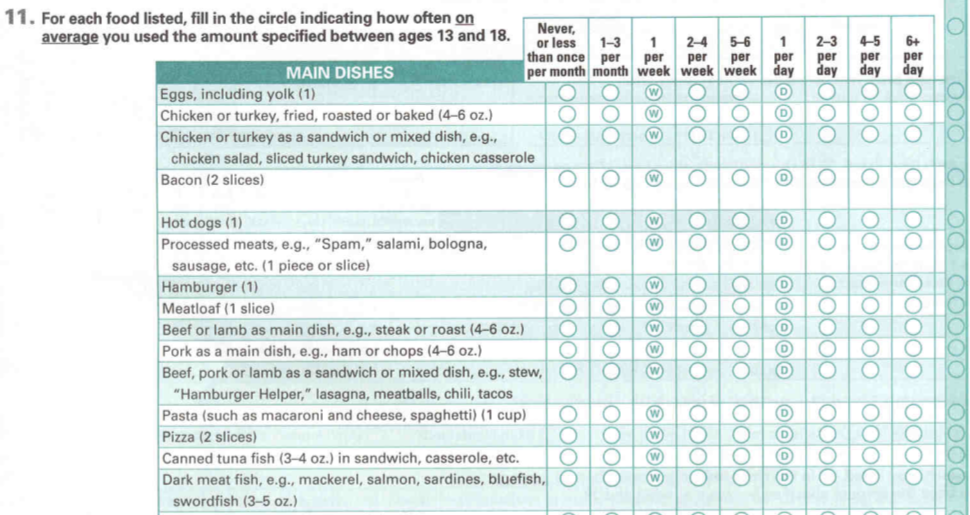

To complicate matters further, a large percentage of these cohorts used an FFQ to assess the baseline intake. Dr. Walter Willet, from the Harvard School of Public Health has demonstrated that FFQs can be quite inaccurate. In one validation study, the foods most accurately reported were tea and beer, while things like meat, fish, bacon, and hamburgers were at best 25% accurate. The subjects filling them out also had a tendency to under-report foods deemed unhealthy while over reporting fruits and vegetables. From the screen shot below of an actual FFQ used in a Harvard study asking adults to answer these questions about their diet as teenagers, it becomes apparent why it can be so inaccurate and subject to bias:

Since the 1950s, saturated fat has been incriminated as the major dietary contributor to heart disease, attributed mainly to the fact that saturated fats have the ability to raise blood cholesterol. This temporary physiologic response to dietary fats led to the logical hypothesis that replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats, which lower blood cholesterol, may also lower coronary heart disease (CHD) rates, cardiovascular mortality, or both. This biological response to saturated fats has been the main reason diets high in meats carry such a stigma. The best way to determine if this hypothesis is true is through randomized, clinical trials. As discussed on our Saturated Fats & Heart disease – Clinical trials page, the evidence from the past 60 years has been inconclusive.

Yet conducting a large, long term trial is tremendously expensive and burdensome. For these reasons, prospective cohort studies offer an alternative design, although no causation can be determined. Subjects can be followed for a very long time and associations between their diets and disease can be illuminated. However, these observational studies (also known as prospective cohorts) have many short comings as well.

When researchers study the possible negative effects of saturated fats in prospective cohorts, they perform a baseline dietary intake measurement (usually a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), 24-hour recall, or 7 day food record), then follow subjects for up to ~25 years. The majority of them do not assess the diet anywhere in between. Just day one (or week one), and year 25.

In other words, What did you eat today, then in 25 years I will check to see if you died of heart disease. If you did, then I will correlate that with your diet the day I asked you what you ate.

Of course the likelihood that the baseline assessment is representative of their diet for the next 25 years is low. The best baseline assessments were 7-day food records, where subjects meticulously weigh and record everything they ate. These were rare.

To complicate matters further, a large percentage of these cohorts used an FFQ to assess the baseline intake. Dr. Walter Willet, from the Harvard School of Public Health has demonstrated that FFQs can be quite inaccurate. In one validation study, the foods most accurately reported were tea and beer, while things like meat, fish, bacon, and hamburgers were at best 25% accurate. The subjects filling them out also had a tendency to under-report foods deemed unhealthy while over reporting fruits and vegetables. From the screen shot below of an actual FFQ used in a Harvard study asking adults to answer these questions about their diet as teenagers, it becomes apparent why it can be so inaccurate and subject to bias:

Never the less, researchers’ attempts to to find a link between saturated fats and heart disease have been unsuccessful for the most part. Some studies have found a correlation, usually of borderline significance, while many have not.

Trying to isolate saturated fats in the sea of nutrients, vitamins, and calories a subject’s diet consists of is difficult if not impossible, and leads to many correlations that may be misleading. For these reasons, it is likely more beneficial to focus on making more practical and tangible changes to the diet, such as eliminating processed foods and sugar or increasing your daily servings of fruits and vegetables.

Bibliography

Siri-Tarino et al (2010). Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease

Outcome: During 5-23 year follow up of 347,747 subjects, 11,006 developed Cardiovascular disease or stroke. Intake of saturated fat was not associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease or stroke. The pooled relative risk (RR) estimates comparing the highest intake of saturated fat to lowest, found that those who ate the most had a relative risk of 1.07 (95%CI=0.96-1.19) for Coronary heart disease, 0.81(95% CI=0.62-1.05) for stroke, and 1.00 (95% CI=0.89-1.11) for CVD.

- Overview: Meta-analysis of 21 prospective cohort studies examining the evidence that saturated fat is associated with cardiovascular disease

- Comments: The most recent meta-analysis, finding no association between saturated fats and heart disease. Researchers also found a non-significant reduced risk of stroke for those consuming the most saturated fat.

Jakobsen et al. (2009). Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies

Outcome: During 4-10 year follow up, 5,249 coronary events and 2,155 coronary deaths occured among 344,696 persons. For a 5% lower intake from SFAs and a cocomitant higher energy intake from polyunsaturated fats, there was a significant inverse association between PUFAs and coronary events: Hazard Ratio: 0.87, (95% CI=0.77, 0.97); for coronary deaths the hazard ratio was 0.74 (95% CI=0.61, 0.89). When replacing 5% saturated fats with carbohydrates, there was a slightly significant association between carbs and coronary events: HR=1.07, (95% CI = 1.01, 1.14); Monounsaturated fats were not associated with CHD.

- Overview: Investigated the association between various types of fats and carbohydrates and heart disease in 11 prospective cohorts.

- Comments: Many of the 11 cohorts chosen did not publish their dietary intake data. The researchers also mentioned that “Dietary intake was determined by using food-frequency questionaire or a dietary history interview…Only baseline information regarding dietary habits was available.”

Cohorts that found no association between saturated fat and heart disease:

| Study | Sample Size | Sex & Age | Average time to follow up | Diet Assessment | # of diet assessments after baseline | Saturated Fat associated with CHD? |

Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamagishi et al 2010 | 58,453 | Men & Women 40-79 | 14.1 years | FFQ | None | NO | SFAs were inversely associated with stroke | |

| Leosdottir et al 2007 | 28,098 | Men & Women | 8.4 years | 7 day food record, FFQ, interview | None | NO | ||

| Xu et al. Strong Heart Study 2006 | 2,938 | 47-79 | 7.2 years | 24-hr Recall | None | NO. When stratified by age, Yes for those 47-59 | ||

| Jakobsen et al. 2004 | 78,778 | Women | 16 years | 7 day weighed food record; FFQ for a subset | 4 times | NO. Only benefit seen when stratified by age: Women <60 showed benefit: HR=2.48 (95% CI=1.3-4.77) | ||

| Ascherio et al 1996 | 43,757 | Men 40-75 | 14 years | FFQ | 3 times | NO | ||

| Pietinen ATBC study 1997 | 21,930 | Men 50-69 | 6.1 years | FFQ | None | NO | ||

| Fehily et al. Caerphilly study 1993 | 2,512 | Men 45-59 | 5 years | FFQ, 30% received 7 day food records | None | NO | ||

| Posner et al. Framingham 1991 | 859, further divided by age | Men 45-55 and Men 56-65 | 16 years | 24-Hr Recall | None | NO | ||

| Farchi et al. 1989 | 1,536 | Men 45-64 | 20 years | FFQ | None | NO | Higher saturated Fat consumption in the lower risk group | |

| Khaw et al. 1987 | 859 | Men & Women 50-79 | 12 years | 24-Hr Recall | None | NO | ||

| Kromhout et al. Zutphen Study 1984 | 871 | Men 40-59 | 10 years | FFQ and interview | None | NO | ||

| Gordon et al. 1981 | 16,349 | Men 45-64 | 6 years | 24-Hr Recall | None | NO | ||

| Garcia-Palmieri et al. Puerto Rico Study 1980 | 8,218 | Men 45-64 | 6 years | 24-Hr Recall | None | NO | ||

| Yano et al. Japanese in Hawaii 1978 | 7,705 | Men 45-64 | 6 years | FFQ, 24-Hr Recall, validation in subset with 7-day food record | None | NO | ||

| Morris et al. 1977 | 337 | Men 30-67 | 20 years | 7 day weighted food record | None | NO | ||

| Paul et al. 1963 | 5,397 | Men 40-55 | 4 years | Interview with Dietitian | None | NO |

Prospective evidence that saturated fat intake is in fact associated with heart disease:

| Study | Sample Size | Sex & Age | Average time to follow up | Diet Assessment | # of diet assessments after baseline | Saturated Fat associated with CHD? |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanasescu et al. 2004 | 5,672 | Women | 18 years | FFQ | 3 times | YES for age adjusted model; RR=1.29; NO for multivariate model or after adjusting for other fats | |

| Oh et al. 2005 | 78,778 | Women | 20 years | FFQ | 4 times | YES for age adjusted model in 2 highest quintiles; No for multivariate RR | |

| Hu et al. 1997 | 80,082 | Women 34-59 | 14 years | FFQ | 3 times | YES for age adjusted model: RR = 1.38; NO for multivariate model or after adjusting for other fats | |

| Esrey et al. Lipid Research Clinic 1996 | 4,546 | Men & Women 30-79 | 12 years | 24-Hr Recall | None | YES. RR= 1.11(95% CI= 1.04-1.18) | Difference in CHD deaths vs. No Deaths was 3 grams of Saturated fat |

| Kromhout et al. 1995 | 12,673 | Men 40-59 | 25 years | Food record in small sub sample | None | YES | |

| Keys et al. 7 Country study 1986 | 11,579 | Men 40-59 | 15 years | 7 day food record | None | YES | |

| Kushi et al. Ireland-Boston study 1985 | 1,001 | Men | YES | ||||

| McGee et al. Honolulu study 1984 | 8,000 | Men 45-68 | 10 years | 24-Hr Recall | None | YES |